“He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby becomes a monster”, Friedrich Nietzsche famously observed. Some might argue that the only monsters in the glamorous world of fashion are it-girls’ favorite ‘ugly’ sneakers, but growing concern about how aggressive public condemnation of plagiarism, cultural insensitivity and various misbehaviours of market players affects the industry dynamics is an important question that many find themselves asking. After all, are we witnessing growing social consciousness that drives a more transparent and inclusive society, or are we simply entertaining ourselves with a new breed of cyberbullying?

Take the recent downfall of Dolce & Gabbana that caused the brand to be banned from the Chinese market – practically overnight. To be fair, the two designers are no strangers to controversy that usually results from their unfiltered comments and polarizing views; yet it’s instructive to see the evolution of the public’s reaction to said controversy – and actions derived by the company.

Simple example: what did we do before in an attempt to hold the duo accountable for their unprofessional (at the very least) rhetoric? In 2015, together with Sir Elton John, we’d #BoycottDolceGabbana for saying that children born through IVF were ‘synthetic’ – and yet the company closed 2015 with a record-breaking revenue of $1 billion. Moreover, the popularized hashtag soon became Dolce & Gabbana’s own mock marketing tool, as it was placed on D&G T-shirts and sold at $245 each.

Many common people as well as industry insiders and even celebrities (especially those who suffered first-hand at Stefano Gabbana’s unpleasant commenting activity on Instagram), patiently waited for the bubble of controversy surrounding the brand to finally burst – and their patience was rewarded to the max when Gabbana’s hateful messages to a Chinese girl were exposed – following a series of PR fiascos with the infamous ad of a Chinese model trying to eat pizza and other Italian delicacies with chopsticks. Results? The company supposedly lost a third of their revenues as they were removed from Chinese shops and rushed into cancelling their grand Shanghai fashion show that was scheduled for the very next day. The problematic duo was forced into issuing a half-hearted apology and went into media exodus, as they were announced ‘cancelled’.

‘Cancel culture’, more commonly referred to as ‘call-out culture’, is a mostly digital movement of refusing to support, promote or follow personas and brands that seem to defend views and beliefs that are nowadays assumed to be, well, ‘problematic’ – which is a surprisingly broad category that goes far beyond simplified assumptions about what is considered to be racist, sexist, homophobic, culturally insensitive or in any other way offensive or even simply ‘tone-deaf’ behaviors. The movement is, of course, not exclusive to the fashion industry, as one might recall wide anger and frustration brought by the #MeToo movement that resulted in iconic Hollywood powerhouses like Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey being ‘cancelled’ for sexually assaulting their colleagues in the film industry.

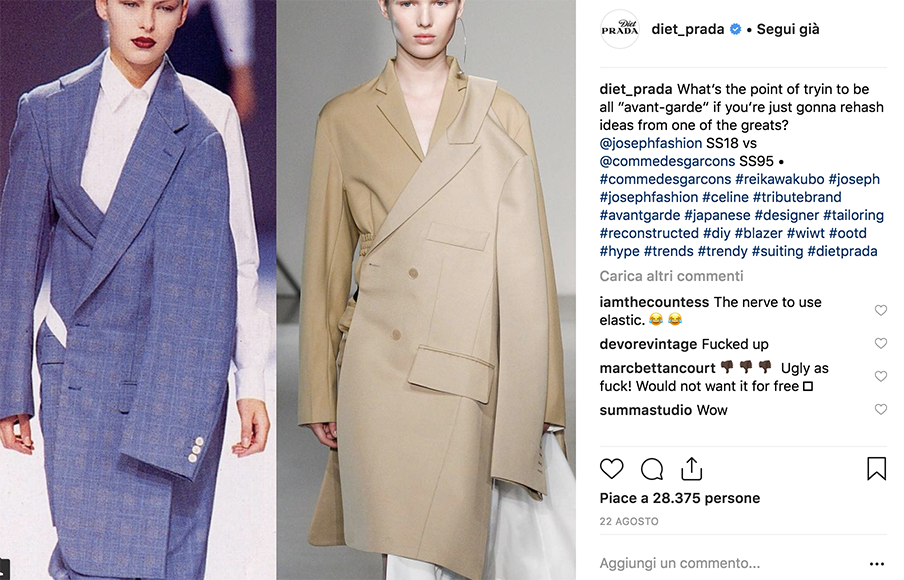

But it is specifically within the fashion industry that call-out culture, often deemed as problematic on its own, took a somewhat unnecessary turn. Enter: Diet Prada – an Instagram account with over 1 million followers, the ‘digital watchdog’ (cit. The Business of Fashion) of the fashion world. Four years ago, in the beginning of their blogging career, the two industry insiders who run the blog to this day were simply shining spotlight on well-known and established brands ‘knocking off’ clothes of emerging, lesser known designers. Side-by-side photo comparisons and launch dates spoke for themselves. Diet Prada was some incarnation of Robin Hood in the world of authors’ rights. In fact, Diet Prada wasn’t the first blog to point out cases of fashion plagiarism, however, it is only when their ‘call-outs’ shifted towards being based on their own views on inclusivity and tolerance, instead of just on examples of copycat behaviors, is when they got noticed, with the Dolce & Gabbana scandal sealing their success; it was ‘DP’ who first posted Gabbana’s racist rants about Chinese people.

To this day, finding yourself on Diet Prada’s account is a PR manger’s worst nightmare. The call-outs are even more damaging for independent bloggers – imagine waking up one morning to being shamed in hundreds of Instagram comments for not taking enough time to come up with original ideas for your collaboration with yet another casual wear brand. As for the brands, different companies respond to criticism in different ways, but mostly are usually forced to issue apologies and pull down products or posts that were denounced as offensive by ‘dieters’.

At which point cancelling people for indecent (but not straightforward illegal) behaviors went all wrong? Writer David Brooks compares call-out culture to ‘tribal mentality’ – a mindset that “depersonalizes everything and reduces it to a black and white struggle of good versus evil. This eliminates proportionality and removes the distinction between R. Kelly and a high school girl sending a mean emoji.” Indeed, there is a major difference between getting away with assaulting underage girls and getting away with being a style copycat or even a ‘bigot’ (a common insult among ‘dieters’), yet the response that the world of online allows us, as a community, to give, is fundamentally the same for R. Kelly and a random blogger, as is the damage caused to their career.

Media lynching logically provokes either defensiveness or insincere apologies. Sometimes, past tweets and comments are digged out to further pressure the entity in question, rightfully rising a question of whether a person should apologize for making a mean comment ten years ago. When being shamed online, it is believed that there is no right way to apologize, as Diet Prada and other self-proclaimed ‘detectives’ will also disregard the apology – partially to keep the topic afloat for a longer period of time in a vicious circle of never-ending guilt trip. It is a behavior largely condemned in corporate environment as demoralizing and inefficient – you cannot criticize your co-workers without offering a solution, and criticism is expected to be constructive. Yes, maybe in the course of history, revolutions presumed that certain kings and queens had to be punished to ‘show ‘em’, but reforms were eventually introduced, too – something that Diet Prada does not seem to be interested in.

Ironically, Diet Prada, who used to pride themselves on being an independent voice, now engage in paid collaborations and sit front row at fashion shows of Prada, Valentino and the likes, making their audience question their authenticity and objectiveness. They have also slipped into general, non-fashion related critique towards certain identities (i.e. the Kardashian-Jenner family) that were largely perceived as borderline bullying and even anti-feminist. Funny enough, Diet Prada themselves are extremely defensive about their policies, causing many people who once embraced the cancel culture to grow fed up with it, noticing how witty call-outs and ‘clapbacks’ are connected to the number of social media likes.

To sum up, it lately seems as if already problematic call-out culture is now being reduced into mock culture, reminiscent of the whole town gathering to watch a Medieval penalty out of simple boredom. Stoning a person’s career for a single mistake is the praised norm, and there is no way for a brand or an influencer to apologize for the situation in the ‘right way’ – it simply does not exist. Consequently, he tension between producers and consumers intensifies further and becomes increasingly frustrating for the damaged party, and redemption always looks forced. But while perpetuating this uncomfortable feeling is justifiable for the #MeToo movement (which, however, has questionable aspects such as false accuses) since it deals with abuse of power and sexual exploitation, it seems to be blown out of proportion in terms of severity when it comes to the production of fashion content and consumer goods.

Perhaps the issue should be addressed through dialogues and regulations – wasn’t John Galliano fined for sharing his anti-Semitic beliefs in a Parisian café? Didn’t Marni successfully sue Zara for copying? Perhaps we should go from calling out to calling in? Because, it seems, if we don’t slow down on the cancellation, we are risking of having the abyss gaze back at us – as Nietzsche suggested.

By Naira Khananushyan