Introduction:

In the golden era of fashion from the 1920s to the 1950s, a saga unfolded between two designers who had completely opposed visions. Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli thrived in a fashion industry where they exhibited their ideologies, aesthetics, and personal vendettas through their work. Chanel focused on simplicity, adhering to the belief that “simplicity is the keynote of all true elegance.” She aspired to liberate women from the constraints of corsets with simple, elegant dresses and to create fashion for the everyday woman. Schiaparelli, on the other hand, introduced the world to the surrealist movement that was gaining momentum in Paris. She introduced novel designs, such as the shocking pink colour and the trompe l’oeil effect, challenging the norms of the era.

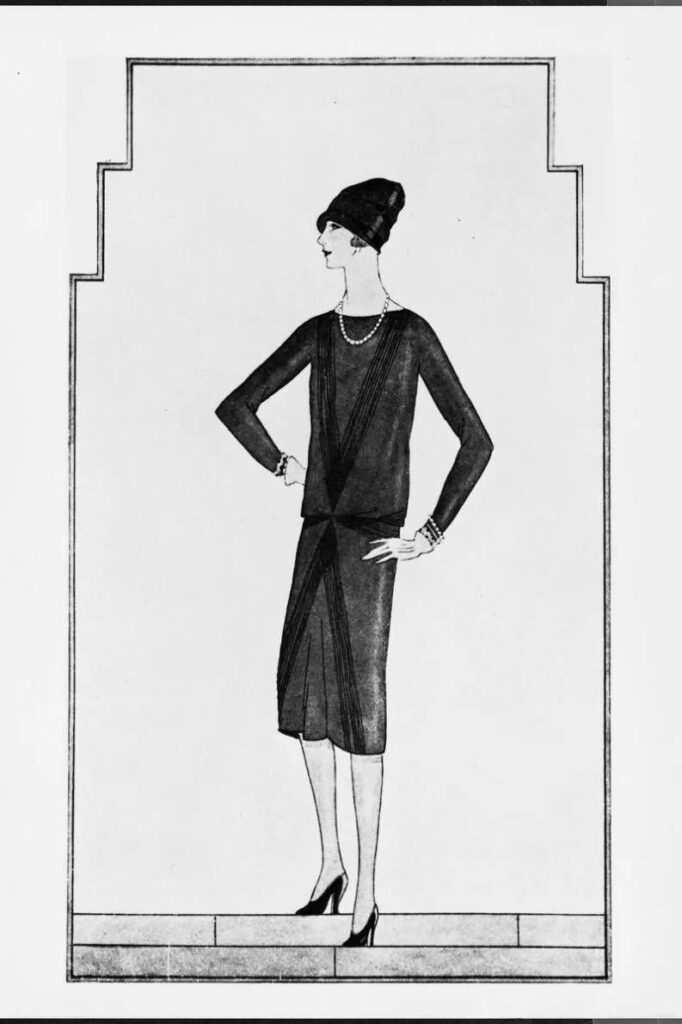

On the left: Chanel illustration of the black dress in American Vogue, 1926; on the right: Zsa Gabor wearing shocking pink for the 1952 film Moulin Rouge.

Chanel’s Emergence and the Wertheimer Feud

Born in 1883, Chanel started to burst onto the scene as a hat maker during a time when women were seeking liberation. During the first world war, many women in Europe took jobs vacated by men who had gone to fight in the war. As women were called up to fill in the gaps, women gained socio-economic power. Fashion, mirroring day-to-day life, needed to reflect the new roles women were taking on, which led to the introduction of Chanel’s simple elegance.

This matched the zeitgeist of the 1920s, where women wanted to showcase their newfound freedom, aligning perfectly with what Chanel offered. She started to experiment with jersey, a breathable and inexpensive knit fabric. Chanel was the first to use it as outerwear as it is a lot more comfortable to wear and women wanted more practical clothes.

Following her success with jersey and opening her own couture house, she launched Chanel N°5 perfume with Bader, founder of the Paris Galeries Lafayette, and the Wertheimer’s brothers, directors of a perfume house. This business agreement led to a heated relationship with the Wertheimer family, as Chanel was unhappy with her 10% cut of the business. The legal battles that ensued were intensified by the start of World War II, as Chanel’s showcased her ruthless side.

During the Nazi occupation of France, Jewish people were banned from owning businesses. Seizing the opportunity, Chanel sought control of her perfume company as the Wertheimers were Jews. Anticipating her move, the Wertheimers cleverly transferred ownership to a friend who was not Jewish. Post-war, Chanel renegotiated with the Wertheimers, only for her couture relaunch to fail disastrously, leading her to hand over all ownership to them in exchange for the Wertheimers to pay all Chanel’s expenses until she would die. Despite these challenges, Chanel’s brand thrived posthumously under the management of Alain and Gerard Wertheimer and the creative direction of Karl Lagerfeld.Bottom of Form.

Schiaparelli’s Surrealist Influence

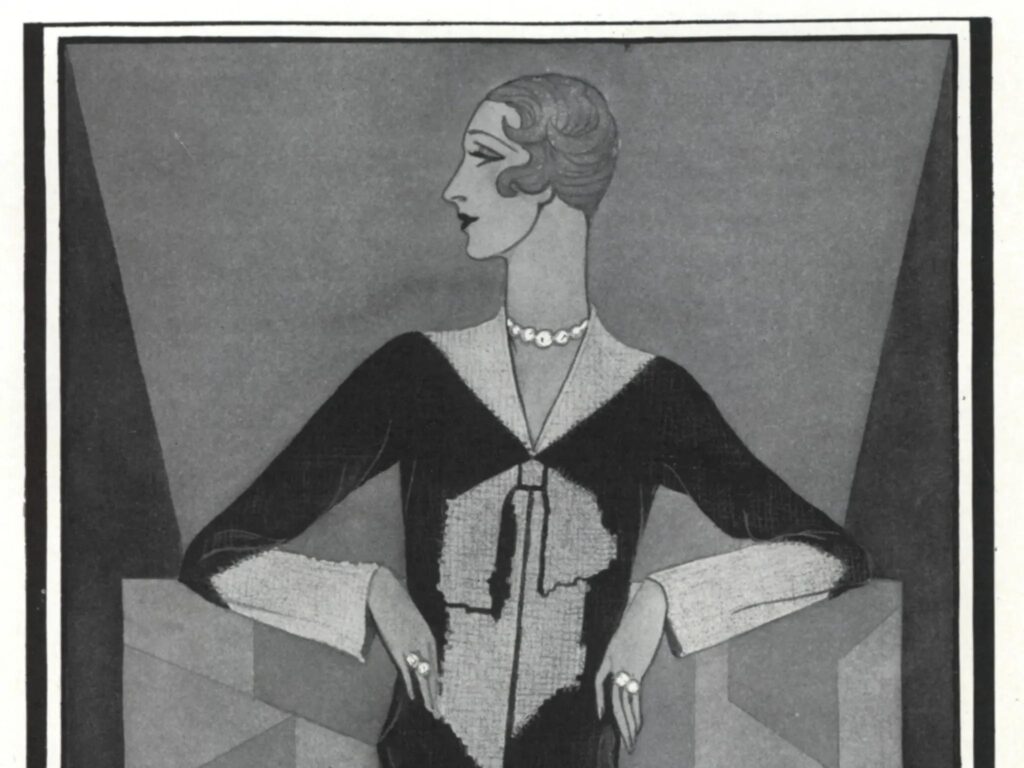

Schiaparelli, hailing from a wealthy Italian family, initially married in haste and soon sought a new beginning in Paris, which was becoming the cultural epicenter of the time. Drawing close to artists like Salvador Dali, she was inspired by the idea of transcending the real world. Despite having no formal training in fashion, she made a tromp l’oeil bow dress.

Her trompe l’oeil bow dress became an instant sensation, leading to more audacious designs like a hat shaped as a shoe, oversized insect pins, and the infamous lobster dress worn by Wallis Simpson, the new wife of the newly-abdicated King of England.

Simpson’s decision to switch from Chanel, a brand she had long trusted, to having Schiaparelli design her wedding dress signified a pivotal shift in fashion—from Chanel’s classic elegance to Schiaparelli’s surrealist flair. Schiap also captured the attention of all Hollywood actors until World War II disrupted the industry.

Schiaparelli struggled to regain her footing post-war and her brand ceased operations in 1954. Yet, the brand Schiaparelli was eventually revived in 2013. Under the creative direction of Daniel Roseberry, the brand has seen a resurgence, not by imitating Elsa’s past works but by channeling her spirit to continue shocking the world.

The Rivalry

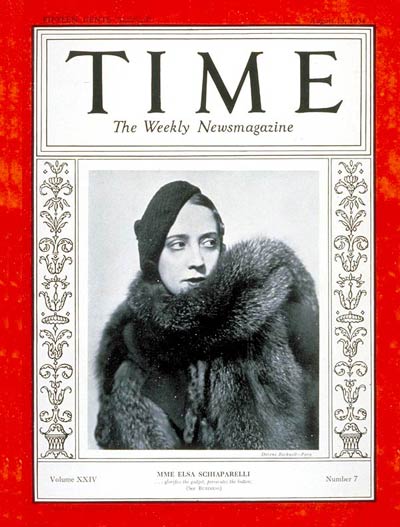

As previously stated, Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli each created distinct and almost diametrically opposed styles. Initially, Chanel was the favorite in the fashion world, but the rivalry intensified with Schiaparelli’s swift rise to fame. Her popularity in the US soared when Time Magazine featured her on its cover. Never was a designer given this honor to the disbelief of Chanel.

The Time cover of Elsa Schiaparelli, 1934

Schiaparelli was stealing Chanel’s spotlight, so she started to publicly call Schiaparelli “that Italian artist who makes clothes.” Then, Schiaparelli called Chanel “that dreary little bourgeois” and “the hat maker”—a nod to Chanel’s beginnings. However, their rivalry reached a boiling point at a pre-WW2 costume ball. Chanel asked for a dance to Schiaparelli. Schiaparelli, dressed as a surrealist tree, twisted and twirled with Chanel, while slowing moving towards a candle. This set the branches of Schiap ablaze, with guests hastily extinguishing the flames with soda water. Their intense rivalry faded after the WW2, with neither achieving significant praise.

Final Remarks

Today, both Chanel and Schiaparelli are thriving legacies of their formidable founders. Chanel’s creations, as fashionable today as in the Roaring Twenties, exemplify Coco’s timeless elegance. She is still seen as one of the biggest names in fashion. Schiaparelli crafted fashion resonating with the evolving world around her. Her intention wasn’t to create everyday wear but to innovate and shock, a mission Daniel Roseberry upholds today. To shock and innovate needs courage and Roseberry’s appeal to the courageous in fashion is evident. Kylie Jenner’s choice to wear the brand’s lion head dress last year is a testament to this. In Gen Z language, if you want to wear Schiap you need to be the main character, while in the 1930s this was called to shock.

Though their rivalry concluded after WW2, the distinctive visions of Chanel and Schiaparelli co-exist today.

By: Boudewijn Welkzijn

Sources

Borrelli-Persson, L. (2022, March 29). A brief history of Elsa Schiaparelli’s iconic bow sweater. Vogue. https://www.vogue.com/article/a-brief-history-of-elsa-schiaparelli-s-iconic-bow-sweater

Chanel vs. Schiaparelli. (2022, June 22). Harper’s BAZAAR. https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/a3781/chanel-schiaparelli-rivalry-1014/

Cinziarobbiano. (2018, January 29). abito-aragosta-lobster-dress-elsa-schiaparelli-wallis-simpson-tbizart. Occhimentecuore. https://eyesmindandhearthaboveall.blog/2018/01/29/considera-laragosta/abito-aragosta-lobster-dress-elsa-schiaparelli-wallis-simpson-tbizart/

Cohen, S. (2012, April 29). The anti-Coco. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2012/04/29/the-anti-coco/

Elsa Schiaparelli and the power of shocking pink. (2020, September 16). ELLE Decoration. https://www.elledecoration.co.uk/decorating/colours/a34011671/elsa-schiaparelli-shocking-pink/

Gostoli, F. B. (2023, July 20). Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli: A tale of scandal and style. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/coco-chanel-elsa-schiaparelli-tale-scandal-style-benvenuti-gostoli/

Hobbs, J. (2021, April 14). These are the perfect LBDs to wear when this is all over. Vogue India. https://www.vogue.in/fashion/gallery/these-are-the-perfect-little-black-dressess-to-wear-when-this-is-all-over

How Coco Chanel changed fashion? – maft magazine. (n.d.). How Coco Chanel Changed Fashion? – Maft Magazine. https://maftmag.com/article/how-coco-chanel-changed-fashion

Lestz, M. (2021, February 17). Best of Enemies: Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli. Margo Lestz – the Curious Rambler. https://curiousrambler.com/best-of-enemies-coco-chanel-and-elsa-schiaparelli/

Rossellamalag. (2023, February 6). Kylie Jenner e la testa di leone alla sfilata couture di Schiaparelli. Grazia. https://www.grazia.it/moda/tendenze-moda/kylie-jenner-testa-di-leone-schiaparelli-sfilata-couture

Shocking Life: The autobiography of Elsa Schiaparelli. (2030, January 11). https://www.bookforum.com/print/1402/shocking-life-the-autobiography-of-elsa-schiaparelli-274

The power behind the cologne. (2002, February). NY Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/02/24/magazine/the-power-behind-the-cologne.html

TIME Magazine Cover: Elsa Schiaparelli – aug. 13, 1934. (1934, August 13). TIME.com. https://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19340813,00.html